3.2. Resolution of the linear elasticity system with the Finite Element Method¶

This section deals with the use of the Finite Element Method for the solution of the linear elasticity system. Much of the treatment of this system is very similar to that of the Laplace equation and its avatars, discussed in Section 1.4.

3.2.1. The variational setting for linear elasticity¶

The variational formulation for this problem reads:

The well-posedness of this problem follows from the classical Lax-Milgram theory, described in Section 1.2. The only missing ingredient is the following result.

Proposition 3.2 (Korn’s inequality)

Assume that \(\Gamma_D\) has non empty surface measure. Then there exists a constant \(C >0\) such that:

The intuition about this result is the following: the displacement functions such that \(e(\u)=0\) are the rigid-body motions, i.e. the compositions with translations and rotations. The rigid-body motions that vanish on a region of \(\Gamma_D\) with positive surface measure must be zero.

Making this idea mathematically rigorous is quite difficult, and it goes beyond the scope of this book; we refer to Th. 6.3.4 in [Cia21].

Exercise

Prove the well-posedness of the variational problem by admitting Korn’s inequality.

Exercise (A study of rigid-body motions)

Bla bla

3.2.2. Resolution of a basic problem in linear elasticity¶

3.2.2.1. A basic resolution example¶

Use of variational formulations over tensor product spaces.

Situation; connecting rod in internal combustion engines? The small end of the rod is connected to the piston, and it undergoes linear motion (i.e inhomogeneous Neumann). The big end is connected to the cranckpin (homogeneous Dirichlet B.C.), and the goal of the device is to convert the input linear motion into rotational motion.

Calculation of stress

3.2.2.2. A complement about vizualization of vector fields¶

Vizualization: - Vector fields with medit - How to toggle a displacement with medit.

3.2.3. A bimaterial situation¶

Or multi-material, like in ferrite. Observe the deformations of the different materials, depending on the Young’s modulus.

3.2.4. Vibrations in an elastic structure¶

This section deals with the calculation of eigenvalues of the linear elasticity system. It is the counterpart in this physical context of Section 1.7.

3.2.4.1. A few words about resonance of mechanical structures¶

Such modal analysis is very important in structural engineering, where for instance, a structure may continue to vibrate and take the form of the corresponding mode, when submitted to motion at this particular frequency (earthquake, pedestrians on a bridge).

Resonance frequencies are particularly harmful, especially when damping is low. Then, even a very small amount of input energy can result in large deformations.

Let us consider a volumic load \(\f(t,\x)\) depending on time and space. One can prove that the elastic displacement is the solution \(\u(t,\x)\) to the time-dependent version of the linear elasticity system:

3.2.4.2. Numerical computation of structural resonances¶

Shear wall example (crane? Mast?)

3.2.5. The ersatz material method¶

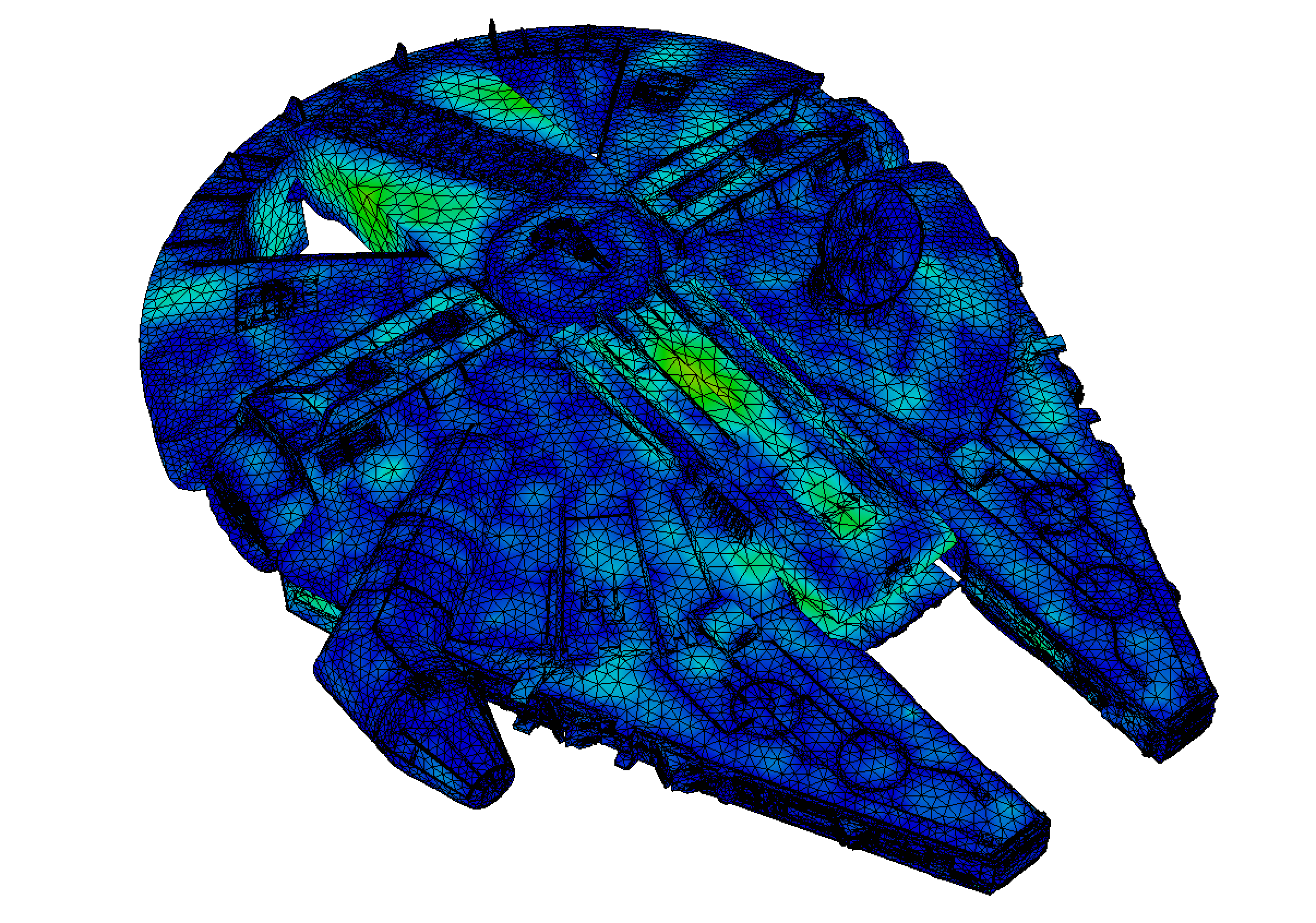

3.2.6. A 3d example¶

A beam with an I shaped cross-section.